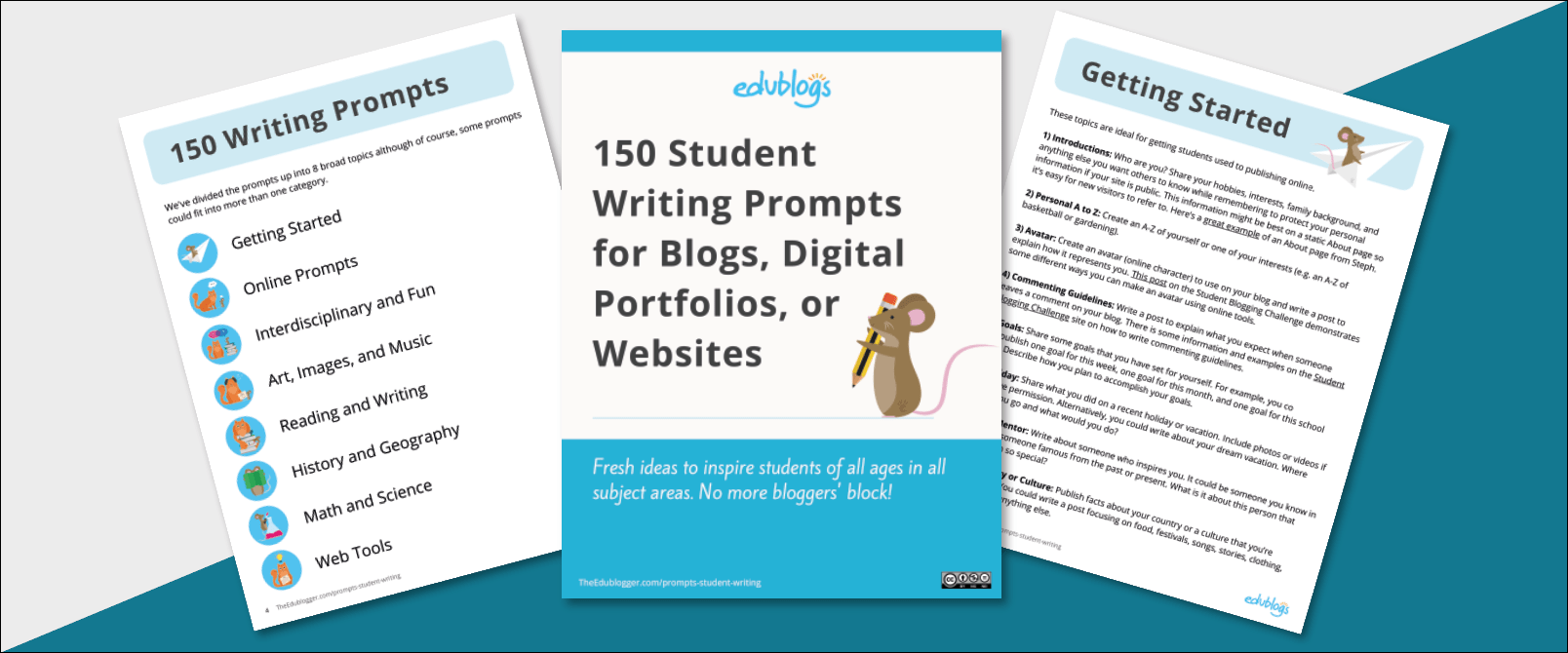

Arts classes and field trips can provide students with “a window into a broader world filled with different people and ideas.” PHOTO BY PRAGYAN BEZBARUAH FROM PEXELS

Education policymakers have seen arts classes and cultural field trips as far less important than reading and math skills. Now there’s evidence that those experiences can have significant benefits, especially for disadvantaged students.

An overwhelming majority of Americans believe the arts are part of a well-rounded education. But for the past 20 years, policymakers have prioritized reading and math and assumed that taking time away for other subjects would cause test scores to stagnate or worse. As a result, the amount of time schools devote to the arts—along with social studies and science—has declined dramatically.

But a flurry of recent studies shows a range of benefits from cultural experiences—some as minimal as going to see one play or spending half a day at an art museum. Researchers led by University of Arkansas professor Jay P. Greene have found that those experiences increase students’ tolerance, empathy, and ability to understand life in another time and place, as measured by survey questions. The effects are strongest for disadvantaged students, perhaps because it’s their first exposure to a museum or live theater.

A larger-scale experiment in Houston found “remarkable impacts” from school partnerships with arts organizations that provided multiple experiences involving theater, dance, music, and the visual arts. Students who got those experiences had fewer disciplinary infractions and better writing scores, compared to a control group. Elementary students were more likely to be engaged in school and aspire to attend college. Also—like the students who visited the art museum and saw the play—all students showed increased “compassion for others.”

Why should exposure to the arts make students more compassionate? Greene speculates that cultural activities “are like looking through a window into a broader world filled with different people and ideas.” A teacher involved in the Houston experiment observed the effect on first-graders of a play they saw about bullying: “You felt like you were in that story. By the end of the story they were able to answer why [bullying] wasn’t good, and why you shouldn’t act this way.” (Live theater was shown to have a more powerful effect than a movie version of the same story.)

You could argue that if exposure to the arts boosts empathy, that should be enough—not to mention its intrinsic benefits, like enjoyment of music. But, some will say, will it do students much good to be empathetic or appreciative of music if they can’t read or do math? There’s evidence that young children who get music lessons derive neurological benefits that could help with processing language or mathematical problem-solving.But to many, that’s not as convincing as test scores.

In fact, one study—involving students who went on multiple field trips—did find an increase in reading and math scores. Another, using less reliable methodology, showed that students in elementary schools with “superior” music education programs scored about 20% higher on reading and math tests than those in demographically similar schools with lower-quality programs. But there were no such effects in the Houston study, although the researchers point out that at least there weren’t any negative effects—so schools needn’t worry that making time for arts education will cause scores to suffer.

But test scores rarely reflect what’s happened during a single school year, let alone as a result of one or even ten cultural experiences. Especially when it comes to reading, standardized tests essentially measure the general knowledge that students have been able to accumulate over a period of years. If students don’t have enough background knowledge and vocabulary to understand the passages on the test—which cover a random selection of topics—they won’t be able to answer the questions.

Children with better educated parents pick up that kind of knowledge at home or through afterschool activities. The rest depend on school. But their schools, grappling with low scores, are more likely to eliminate social studies and science—and the arts—in favor of reading and math test prep. The result is that the students who rely heavily on school to acquire knowledge are the least likely to get it there.

Whether or not the benefits of arts education and field trips are captured in test scores, it’s clear they can expand children’s knowledge and vocabulary. Even after just one trip to a museum or live theater, Greene saw students “absorb a high amount of content knowledge.” Imagine the impact if those experiences were woven into a coherent curriculum instead of being one-off events: they could build on and reinforce knowledge that students were acquiring systematically. Imagine, for example, if students had already learned something about the artists or the historical context surrounding what they saw at the museum, or if they’d read “Twelfth Night” before seeing a performance.

These kinds of excursions shouldn’t be reserved for older students. The effects of field trips are particularly powerful for students in kindergarten through second grade—perhaps because, like disadvantaged students generally, it’s likely to be their first time at a museum or a play. And young children are most likely to retain information when there’s an experience to go with it. Preschool teachers have told me how much their students have gained from visiting, for example, a river when learning about the concept of watersheds, or a museum exhibit linked to a particular artist they’ve studied. And history—generally, but mistakenly, thought to be too abstract for young children to grasp—can come alivewhen combined with trips to old houses or historic sites.

In-school arts education can also be a powerful lever for building knowledge and vocabulary along with student engagement. I’ve seen second-graders—in a high-poverty school that used an atypical curriculum—practice a skit about Persephone’s abduction by Hades, reinforcing newly acquired knowledge. In dance class—in addition to getting an opportunity to move around—they acquired knowledge about ballet and new words like plié. In the many schools that adhere to a narrow reading-and-math curriculum, arts classes can be particularly valuable. One teacher I know was so frustrated by the focus on test prep at her school—even though she was teaching first grade, and state tests don’t begin until third—that she switched to teaching art; part of her plan was to teach concepts like juxtaposition and contrast through art, since she hadn’t had the freedom to do that as a literacy teacher.

There are signs that experiential learning is on the increase—and that it’s going beyond the arts, valuable as they may be. In D.C., one organization called Capital Experience Lab is using the holdings of the Smithsonian Institution as the basis for curricula in science and history, and another called Live It Learn It partners with high-poverty schools to provide not only educational field trips but also related materials for teachers to use in class. And while Greene is now studying the effects of a ten-day trip abroad, the D.C. public school system is already providing such trips—fully funded—for middle and high school students.

But it’s far from clear that additional money for these initiatives—or for the research that might validate them—will be forthcoming. Greene notesthat while parents, teachers and those affiliated with arts organizations have all been enthusiastic about his studies, the foundations that fund education reform are distinctly uninterested. Perhaps their staff needs to recognize that the test scores they place so much weight on are unlikely to improve unless they adopt a broader definition of “student achievement.”

[“source=forbes”]