“My husband drank a lot and was short-tempered, but he was a good man,” she said. “But my brother-in-law was a drunkard who made me feel unsafe, so I took my sons and fled to my mother’s house.”

When Maske moved back to her parents’ home in Chakan, an expanding village 50 kilometres from Pune, she was 25, newly widowed, and a single mother to two toddlers. Her husband had been working as a laboratory technician at a private hospital in Pune. Instead of his pension, the hospital offered Maske a job as an ayah or attendant.

She had never worked outside the four walls of her home before. Her mother Tara, 65, prepared Maske for her new life out of doors. “I told my daughter to continue wearing her mangalsutra and sindoor, and I told her not to wear white at all,” said Tara, who herself had been widowed when her children were still teenagers. “The world is not kind to women without husbands.”

Life in a hospital

Maske’s job involved working six-hour shifts six days a week, and a 12-hour shift once every fortnight, and it paid Rs 1,700 a month. Her daily commute by bus between Chakan and Pune consumed a further four hours at the least.

She works as attendant to the nurses – a job description that includes everything from giving patients sponge baths to administering bedpans. There are more than 350 nurses and attendants at the hospital where Maske works, the majority of them women.

“There are a few male nurses and several male attendants, but women attendants like me have to help both female and male patients,” said Maske, who had no training and learnt on the job. “Male attendants don’t attend to female patients unless they need to be lifted from beds and chairs.”

The growth of private hospitals has opened up many jobs in the healthcare sector for women like Maske, but there is a flip side. “Sometimes, working with male patients can be uncomfortable because they deliberately use offensive language with women attendants or harass them,” said Maske. “I haven’t personally experienced any such incident, but some of my colleagues have.”

Harassment of women in the healthcare sector is common but often goes unchecked, according to a report by the non-profit Center for Enquiry into Healthcare and Allied Themes. “There is nothing much that can be done about harassment or improper behaviour, though, because the hospital management is likely to take the patient’s side,” said Maske.

Dream house

It took her eight years of hard work and saving to build herself the home that her mother dreamed of – and all through that slog, her mother Tara was both strength and inspiration. Tara, who had never been to school, spent most of her life working as a domestic help in Mumbai and moved to Chakan, her hometown, only after her husband’s death. She had four children to raise alone, and she set up a small canteen for labourers working in factories around the village.

Despite her lack of education, Tara had a knack for business. Through the 1990s and 2000s, Chakan grew into a major industrial hub in Pune district, and Tara adapted her canteen to suit the needs of the growing market. She built herself a spacious house in the village (“a house with a toilet”), got all her children married, and encouraged her daughters-in-law to work.

Now, with her children and grandchildren running the canteen, Tara is living a life of retired ease. “In the past few years, I have travelled everywhere from Kashmir to Kerala, visiting different temples,” said Tara. “And my youngest daughter has moved to America with her husband – who would have imagined that?”

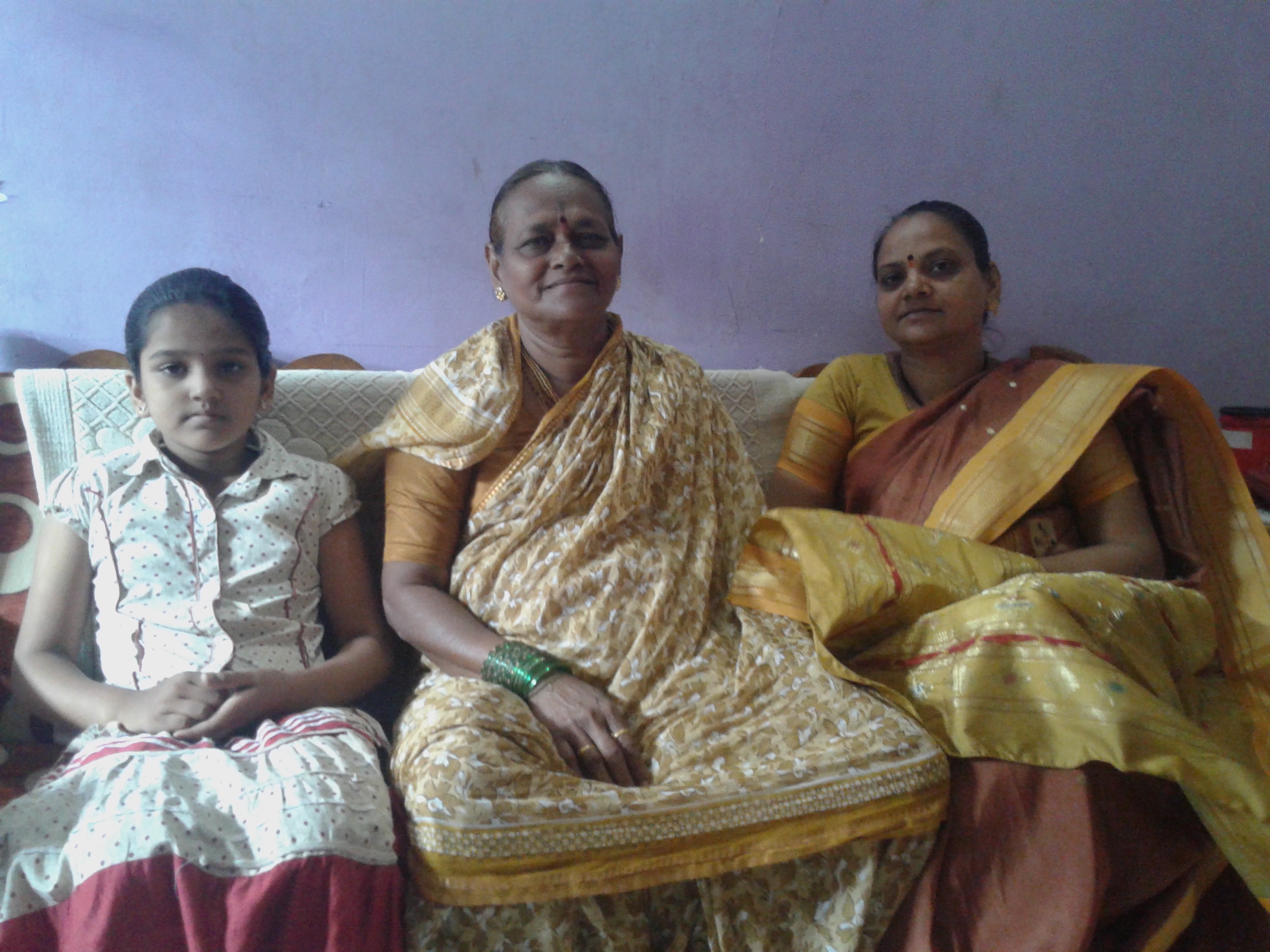

Tara (centre) with her daughter Manju Maske and one of her many grandchildren.

Manju, Tara’s elder daughter, has worked just as hard in the past 15 years to build an impressive life for herself and her sons. In 2007 she pooled in her savings, sold her jewellery and bought a small, one-bedroom flat in her own name in one of Chakan’s new apartment blocks.

“I needed to get my own place. My mother has always been by my side, but how long could I be a burden on my brothers and sisters-in-law?” said Maske. “This is a good building but sometimes, without a man in the house, society makes it difficult for women.

“You have to learn how to deal with sleazy looks and perverted attitudes. If any man visits my house, for instance, some people assume I am having an affair.”

Upward mobility

Maske now earns Rs 15,000 a month at the hospital, is grateful for the security of her own roof over her head, and has just bought a new flat-screen television set. Despite this, she doesn’t believe she has been successful in running her own household. Her sons, she fears, are heading down the path of self-destruction.

The boys, Shubham and Rishikesh, are now 18 and 17. Neither of them have completed school: Shubham gave up the idea of college when he failed his Class 10 exams, while Rishikesh dropped out in Class 9 itself.

“When they were growing up at my mother’s place, most of the adults were working. We made sure that they went to school, but we were not available to ensure that they did their homework or behaved well,” said Maske. When the boys began to play truant, she enrolled them in a boarding school in Pune, hoping that it would instil some discipline. “But they ran away from there in less than 15 days. They just don’t care about education, and they have no life plan at all.”

The two boys haven’t been looking for work either, but they show all the traits of youngsters of the consumerist age. Right after Maske bought the new TV for their home, she says with bitterness, the boys demanded a new sound system too.

“They just don’t seem to understand that I don’t have unlimited sources of money,” said Maske. “I know I have done well for myself, but sometimes I feel I have failed as a mother.”