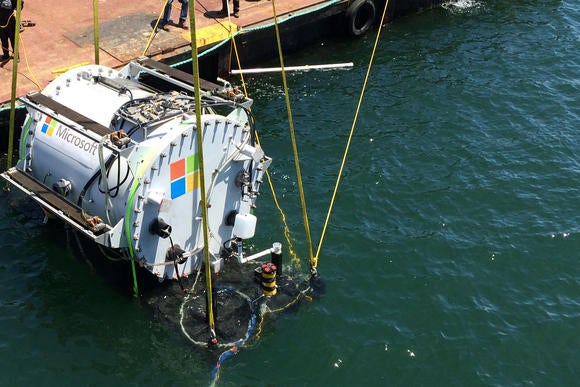

The company’s R&D department recently went public with Project Natick, a data center enclosed in a steel capsule that sits on the ocean floor. These underwater data centers are more easily deployed, reduce emissions, and save a ton of dough on cooling compared to traditional server farms, at least in theory.

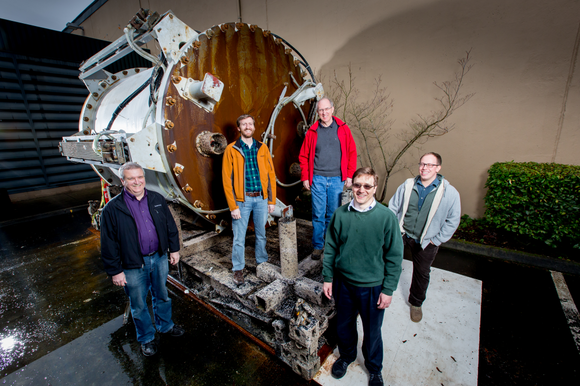

Microsoft already completed its first successful mission last year. Between August and November of 2015, the company deployed its first prototype vessel, the Leona Philpot, which was named after a character connected to the Halo series. That first vessel contained one server rack, according to The New York Times, surrounded by pressurized nitrogen to remove heat from the components.

Project Natick capsules are designed to last for 20 years, coming out of the water every five years to swap out servers.

The story behind the story: Data centers can show up in the craziest places, and Microsoft is no stranger to coming up with new ideas. In 2011, Microsoft and the University of Virginia teamed up to create the ”data furnace” concept: miniature data centers that could pump out enough exhaust heat to warm a home or even a small office building. Other companies have also come up with interesting ideas for data centers. Facebook built a data center in northern Sweden to save on cooling costs by using the environment’s frigid temperatures. Google also has a data center in Finland that uses sea water as part of its cooling system.

Under the sea in 90 days

Microsoft says underwater data centers would be ideal in many ways. First, they can help reduce cooling costs and emissions from a regular data center by taking advantage of the lower surrounding temperatures for cooling, though the capsule doesn’t actually consume water for cooling.

An underwater capsule can also be built and deployed within 90 days. That’s a great turnaround time if your cloud service needs extra help during a major event like the Super Bowl, when tons of users want to access their data in a specific location. A Project Natick vessel could also be dropped off the coast of a disaster zone to enable faster access to data when it counts.

Finally, about half the world’s population lives within 124 miles (200 kilometers) of the ocean. Placing datacenters offshore brings them closer to more users, which in turn would make latency (the time it takes data to transfer from a server to your PC or smartphone) goes down dramatically.

For now, however, Project Natick is in its early days, and it’s not clear when it might become a viable product, or if it ever will.