We think of the mobile phone — well, what we would call a cell phone — as something fairly modern. Many of us can still remember when using a ham radio phone patch from your parked car would have people staring and murmuring. But it turns out in the late 1940s, Bell Telephone offered Mobile Telephone Service (MTS). It was expensive and didn’t work as well as what we have now, but it did let you make or receive calls from your automobile. After the break, you can see a promotional film about MTS.

The service rolled out in St. Louis in the middle of 1946. The 80-pound radios went in the trunk with a remote handset wired to the dashboard. At first, there were only 3 channels but later Bell added 29 more to keep up with demand. An operator connected incoming and outbound calls and if three other people were using their mobile phones, you were out of luck.

USE CASES AND GEAR

The video shows a truck driving team that receives a call to make an unscheduled pickup, then a worker who calls the main office while out in the field. There were a lot of manual steps to determine what base station to use for the call. It isn’t obvious until close to the end of the video, but the system was half-duplex. You had to push a button on the handset to talk.

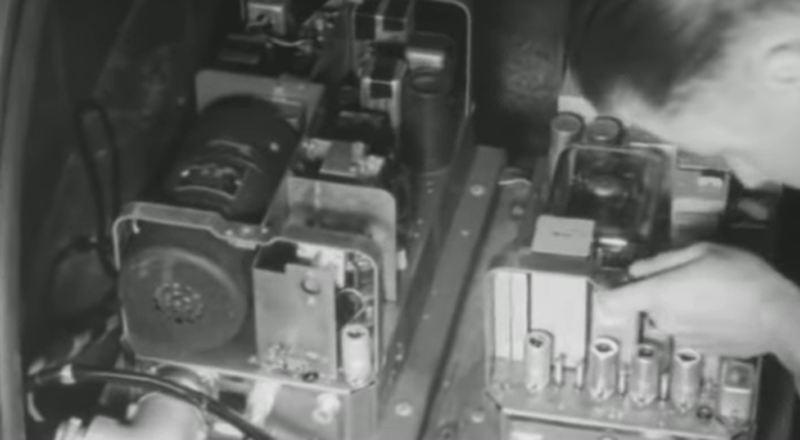

The radio gear shows up around seven minutes. Be prepared. They are going to tell you the two units are “compact!” The dynamotor that supplies plate voltage to the transmitting tubes alone probably weighs 15 times your largest cell phone’s weight. Not to mention there was a possibility your vehicle would need to have a larger battery and alternator installed. As big as these were, the output power was only about 3 watts.

If you want more technical detail and some great pictures, [wb6nvh] has a really good page detailing the history of MTS.

BASE STATION

Around the eight minute mark, you can see the base station antennas and radios. In the middle was an operator sitting at a classic switchboard. There were two services available: an urban service that had radios in cities and the highway service had antennas along major roadways.

The frequency, by the way, was in several bands. The low VHF band was around 40 MHz for the highway service and around 150 MHz — not far from the current 2-meter ham band — for the urban service. At first, you had to listen for the operator to announce your mobile phone number, but this was soon replaced by selective calling as seen in the video.

The frequency, by the way, was in several bands. The low VHF band was around 40 MHz for the highway service and around 150 MHz — not far from the current 2-meter ham band — for the urban service. At first, you had to listen for the operator to announce your mobile phone number, but this was soon replaced by selective calling as seen in the video.

There was a variant of MTS that used shortwave frequencies and single sideband. Of course, that was noisy and finicky. There was also some use of MTS to make public phone calls on a train.

BEFORE CELL

Common sense would make you think that a “good” radio system would have high power and a large footprint. The problem with that is that the larger area invalidates a channel for all users in that area.

The key to successful mobile service was to make transmitters weak and antennas very directional and low range. This allows you to restrict a set of channels to a small region or cell. Those same frequencies can then find use again in a nearby, but not adjacent, cell.

This made it hard to fit too many customers into the mobile system. In some cities, the waiting list was about three years. Prices were high because the systems were often at full capacity so encouraging new subscribers didn’t make sense.

FAREWELL MTS

MTS hung around until the 1980s. But by 1964, the writing was on the wall and Improved Mobile Telephone Service (IMTS) was available. IMTS has direct dialing and full-duplex. A common IMTS phone, the 25 watt Motorola TLD-1100, had two roughly 8-inch square circuit boards to locate an idle channel and do other channel management via audio tones. That is, an idle channel had a 2 kHz tone transmitted, while a busy channel had 1.8 kHz. You could even get an IMTS phone in a briefcase.

MTS hung around until the 1980s. But by 1964, the writing was on the wall and Improved Mobile Telephone Service (IMTS) was available. IMTS has direct dialing and full-duplex. A common IMTS phone, the 25 watt Motorola TLD-1100, had two roughly 8-inch square circuit boards to locate an idle channel and do other channel management via audio tones. That is, an idle channel had a 2 kHz tone transmitted, while a busy channel had 1.8 kHz. You could even get an IMTS phone in a briefcase.

[“source=hackaday”]