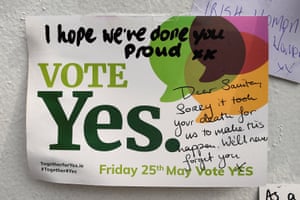

The photograph from the Irish referendum that brought me undone was of white-haired men in the street holding a yellow banner. It read “Grandfathers for Yes”. It came across my phone as I traversed Melbourne in the 86 tram only a couple of days before the vote, like a lobbed bomb of hope and love, relief and change. I sobbed aloud.

It struck with specific weight because there’d been another photo circulating a week earlier of Irish men the same age in a sadly more familiar scenario. “Vote NO” read their own pink signs, “Support women, protect babies, save lives.” That one had left me not in hot tears but a cold rage.

Because this is what we’re more used to, women. The conspicuous lack of solidarity, from those who would pretend to our support but not trust us with the insight to govern our own lives.

You don’t need to watch The Handmaid’s Tale to see pale male authoritarianism at its most extreme iteration. You can see it in one of those art-directed group shots of Trump and his gang of gormless greybeards, striking women’s rights from the ledger with happy sneers and pen strokes. You can see it internationally, across generations of interchangeable, aspirational male totalitarians, always pinning a thousand pseudo-moral justifications on themselves to camouflage an ugly inner truth; the obsession to restrict abortion wells inside from a raw greed to control.

But Ireland has said no to this regime, conclusively. It’s said no to this – now proven – minority of men. And hope burbles where the world as it is has so long encouraged the powerless, the disadvantaged and exploited – so many of them women – to squash and suppress it.

I’m hardly the only woman who the events in Ireland moved to tears. Suzanne Moore confessed to the same emotions in the pages of this publication, and wet eyes met the river of tweets relating the journeys of Irish travelling #hometovote, and why.

I had no skin exposed in this game – I’m Australian, not Irish, and I’ve never had an abortion. My adult life has been dominated by the inability to fall pregnant, my insides wracked with the mess endometriosis has made of them. The old cliches broadcast about womanhood would insist on my jealousy of the pregnant, my resentment of terminations. But, as Ireland has declared at volume, what exists behind the stereotype of “woman” is a human adult, who accepts the world as it is, and, if allowed, can make the best of it on their own terms.

This is why the struggle for reproductive choice is so important – because it destroys that insistent mythology that women are, or should be, unable to determine the best shape of their own existence. Reading the stories of choices made – and sometimes denied – of women pouring forth from Ireland has reminded me of the experiences of friends.

Religious Ann, pregnant in her 20s from an out-of-character one-night stand with a stranger in another country, had a termination, rejoined her community and got on with her life, built a successful career, loving relationship and two beautiful boys. Working-class Jane, with her contraception-proof body, teenage and pregnant – several times – to a junkie she finally found the courage to escape, now suburban and stable, married and safe, with a permanent job, a boy and a girl. And Eileen – gay, pregnant and poor, who never regretted taking her extraordinary pregnancy to term, because she knew that having him was really, truly her choice.

All of these names have been changed because only abortion could stigmatise women for making entirely the right decision. And that’s what the legalisation of abortion vindicates – that, consistently, the implications of pregnancy to mother and child, family and broader society are best made by the woman involved, and no other. One guesses that it’s this powerful capacity for judgment that threatens the greybeards so.The work continues beyond Ireland, of course. There’s still a denial of reproductive rights in Northern Ireland. Campaigns against abortion in America are notoriously horrendous. Less well known is that abortion rights are not entirely confirmed by law for the women of New South Wales, Queensland or the Northern Territory, and lip service to rights does not deliver access to Tasmanian women who, denied safe clinics, must travel to the mainland to receive terminations.The human rights activist Paula Avila-Guillen has been reminding the world in the wake of Ireland that the total denial of rights in the Dominican Republic has seen teenagers fatally denied cancer treatment as because to do so would harm a pregnancy. El Salvador sends women to jail for stillbirths they deem “aggravated homicide”. And Honduras’ marginalisation of women extends beyond total abortion bans to bans on the morning-after pill as well. Unsurprisingly, it also has the second highest rate of teen pregnancy in South America and one of the highest rates of gender-based violence in the world.

And if ever there was a reminder that the campaign against women’s bodily autonomy is a campaign of violence, it would be the death of Savita Halappanavar, the dentist who died from complications of a pregnancy that Irish doctors were prevented by law from terminating. Of all the tears shed over the referendum, could there have been a greater sea than the one created in her memory – from the murals on the walls, the flowers left for her, the cards that read “We’re sorry”. The simple chant of “Savita! Savita! Savita!” that rang out from the crowds in the town squares at the referendum’s victory brought me to floods.

Finally, a woman’s death at the hands of an old madness did not mean nothing. And that the resounding majority of a country can acknowledge it should never have happened at all, now means everything.

- Van Badham is a Guardian Australia journalist

source:-theguardian.