Say the name Lipton, and most people think of tea. But behind that brand lies the extraordinary story of a rags-to-riches tycoon, self-publicist, philanthropist and sportsman who was honoured as “the world’s best loser”.

In early December 1881, a steamer docked in Glasgow, carrying an extraordinary cargo from America. The world’s largest cheese.

The cheese, which was two feet thick and with a circumference of 14ft (4m), was watched by hundreds of onlookers as it was transported by traction engine to the Lipton’s store in the High Street – where it was found to be too large to fit through the door.

Undeterred, the parade continued to the Lipton’s Jamaica Street store (which fortunately boasted a wider doorway) where the cheese was manhandled into the shop window.

Nicknamed Jumbo, for a fortnight crowds marvelled at the spectacle, said to be the product of milk from 800 cows and the labour of 200 dairymaids.

As a publicity stunt it was already a success – but Tommy Lipton had another surprise up his sleeve.

In a ruse worthy of Willy Wonka, he turned the giant cheese into a golden wonder by hiding a large quantity of gold sovereigns inside it.

A few days before Christmas, dressed in a white suit, Lipton began cutting up the monster.

Policemen struggled to maintain order while his assistants wrapped the slices and handed them out to the legion of customers who had gathered in the hope of a lucky purchase.

It was a piece of theatre from a man who was riding a wave of remarkable success, whose grocery stores were spreading far and wide – and a world apart from his childhood in the poverty stricken Gorbals area of Glasgow.

Born in 1848, the son of immigrants from County Fermanagh, across the Irish Sea, Lipton’s first lessons in retail came when his father set up a small shop, selling basic provisions in the overcrowded district on the south bank of the Clyde.

From the age of 10 he was picking up simple foodstuffs in a wheelbarrow from the ships that docked on the river.

The docks and the sailors’ stories fascinated the young Tommy Lipton.

At the age of 15 he took a job as a cabin boy on a steamer. Two years later he had saved enough money for the passage to America.

Various jobs took him to the tobacco and rice plantations of Virginia and South Carolina – but New York was the biggest influence.

On Broadway he found himself working in the giant store owned by another immigrant of Irish/Scots descent, Alexander Turney Stewart.

A marble-fronted palace of consumption, one of the biggest shops the world had ever seen. Stewart was showcasing an entirely new way of shopping.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

“He uses a bunch of strategies that we see Lipton using in his own career later,” explains Museum of the City of New York curator Steve Jaffe.

“Low mark up, high volume. You get a lot of goods, you can sell them and still make money if you sell them at a reasonable rate.

“Set prices – before Stewart you haggled. Merchants, shopkeepers haggled with customers over prices. He does away with that, it’s a set price.”

When Tommy Lipton returned to Glasgow, five years after he’d left, he had still to make his fortune – but now he had a vision of how it could be done.

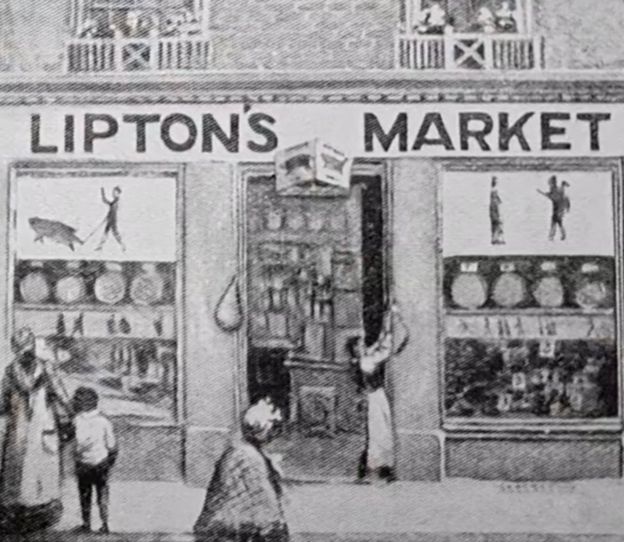

Still in his early 20s, he opened his own store – Lipton’s Market in Stobcross. For Glaswegians it was a very different shopping experience.

“Lipton’s Markets he has on the outside, and he has it brightly painted. Then as you go into the shop, it’s a total contrast from what he knew growing up as a small boy, “says Laurence Brady, director of the Sir Thomas Lipton Foundation.

“He has his sales assistants there in bright white aprons. He has rows of hams, rows of cheeses.

“His shop is very brightly lit. It’s spotlessly clean – and behind the counter you have Mr Charm himself. Anyone walking in, it’s ‘let me show you these offers we have, how affordable they are’.”

No more middle man

It was a recipe for success. Similar stores soon spread across central Scotland- all with the same name over the door. Lipton.

But it was only the start. Lipton knew his business depended on a reliable supply of high quality products, many of them imported. To move onto the next level, he travelled back to County Fermanagh to do a deal.

“He’s looking for Irish produce, because that’s what his customers are wanting,” says genealogist Frank McHugh.

“It’s here he changed his method of operating in his business. He employed someone locally to go out and meet the farmers before they arrived at the market – and guaranteed a price.

“This was revolutionary, it was a totally a new way of doing business. It’s really how the modern day supermarkets work, they go out to the farmers and they cut out the middle man.”

The new approach was so successful, Lipton almost ran out of cash, pawning his gold watch for 30 shillings as he struck deals with the eager farmers.

His stores were now springing up across the length and breadth of Scotland – and always with much fanfare.

Enigmatic billboards and flyers would announce that “Lipton is coming”.

A butter sculpture in the window, a parade of live pigs causing chaos in the city centre – just some of the tricks that made a Lipton store opening a grand event.

But behind the elegant shop facades, lay a business mechanism which powered forward his profits and expansion.

“This was genius,” says latter day entrepreneur Duncan Bannatyne.

“Tommy Lipton didn’t have to rely on any third-party suppliers. He had full control of his supply chain,”

“From the printers, to the packaging, to the distribution, to his network of stores. Tommy had it.”

As Lipton’s stores spread across Britain his next step was to conquer America, once again cutting out the middle man as he purchased an entire meat packing plant and named it after his mother.

Back in Britain, Lipton’s giant cheeses were now regular pre-Christmas attractions. A store manager in Nottingham is said to have hired an elephant to transport one of them through the city.

In 1887 Lipton offered to gift an even bigger cheese, weighing not less than five tons, to Queen Victoria but was politely declined. Whether or not she was amused is unclear.

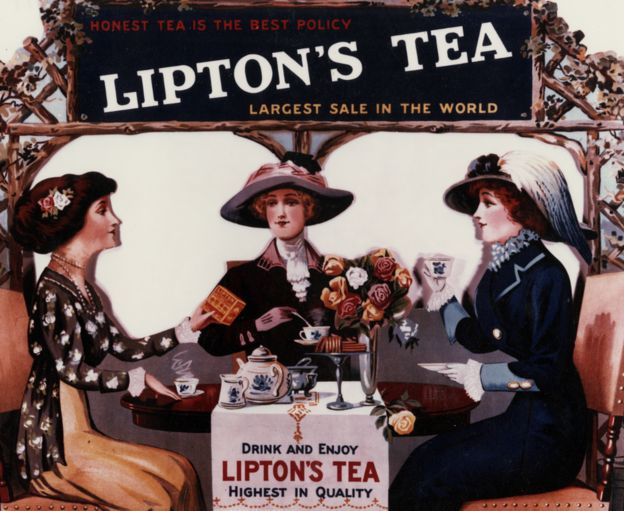

As always Lipton was on the lookout for the next business opportunity – and it came the shape of a foodstuff which remains linked with his name to this day. Tea.

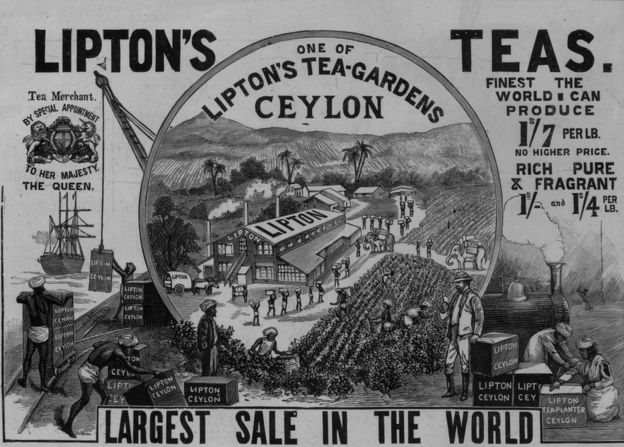

Image copyrightUNILEVER

Image copyrightUNILEVER

It had once been a precious commodity, worth more than its weight in gold, kept in ornate lockable caddies – but by the mid-19th Century the price had fallen, and it was fast becoming the beverage of choice of the Victorian middle classes.

In May 1890, Lipton travelled to Sri Lanka to buy his first tea plantation.

Just like the Ulster farmers who supplied his first shops, they traded exclusively with Lipton stores – and straight away he put his competitors at a disadvantage.

“Everyone bought through the same location – Mincing Lane in London – where teas were blended but the quality was not reliable,” says biographer Michael D’Antonio.

“Sometimes it would be very good, other times it would be mouldy and sometimes you’d buy a packet of tea, and it would all be bad.

“He got the idea to standardise the blend and package it in a way that was consistently fresh and tasted the same when you bought it.”

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

By now his grocery empire had taken the Lipton name into the most fashionable streets of Victorian London.

Lipton himself – the boy from the Gorbals – was mixing with the highest echelons of Victorian society.

When the Princess of Wales, Alexandra decided at alarmingly short notice to organise a charity feast for the Queen’s diamond jubilee celebrations, it was Lipton who came to the rescue with a donation of £25,000 – well in excess of £2m in today’s money.

The following year he was knighted.

“He becomes overnight an A-class celebrity,” says Laurence Brady.

“And all those other characters and skills that he has. He is so charming and he’s so easy to deal with. Everybody loves to be with him.”

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

In 1898, when he floated his company, he retained a controlling interest but pocketed £120m, worth a billion pounds today.

Barely 50 years old, he now had the means to realise a childhood dream.

The Americas Cup

It is the world’s oldest international sporting trophy. The America it refers to is not a country but a boat of the same name, built by members of the New York Yacht Club.

In 1851 they sailed the schooner to the Isle of Wight at the invitation of the Royal Yacht Squadron for a race – and took home an ornate silver trophy.

A few years later they dedicated it to international competitive sailing.

As a boy Lipton was entranced by the ships arriving in Glasgow, making models and floating them in the city’s ponds.

Lipton now joined the world of elite yachting, in his quest for the sport’s ultimate accolade.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

There were strict rules for those hoping to win the America’s Cup. Yachts had to be built in the challenger’s country and sailed to the start of the race. They also had to be members of a yacht club.

But when Lipton applied to join the prestigious Royal Yacht Squadron he discovered even vast wealth and prestige were not always enough to overcome snobbery. They turned him down.

Instead, he joined the Royal Ulster Yacht Club, based in Bangor, County Down.

Lipton’s first challenge in 1899 won the hearts of many Irish Americans.

His yacht was named Shamrock – and while he lost the race, in other ways he was a winner.

Everyone was talking about Sir Thomas Lipton – and Lipton the brand was bigger than ever.

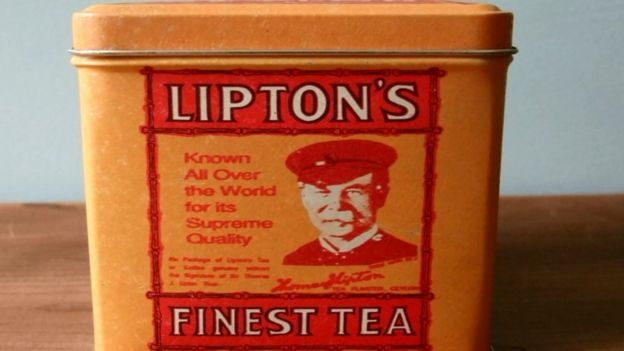

A century before the likes of Richard Branson, Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, Lipton had pioneered the idea of the brand built around an individual.

His face, sporting a yachtsman’s cap, featured on much of his company’s packaging, says food historian Judith Krall-Russo

“Women would like to have photos with him. That was the thing – ‘Oh I have a photo with Thomas Lipton’. It was like Elvis Presley, that’s what it was like, he was a celebrity. People came aligned with him and they would want to buy that brand.”

The visitor book of Lipton’s luxury steam yacht Erin reads like an early 20th Century Who’s Who.

President Roosevelt, Kaiser Wilhelm, the scientists Edison and Marconi.

It is said he banned all talk of religion or politics while on board.

He challenged again for the America’s Cup in 1901 and 1903 with new yachts, Shamrock II and III – again without success.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

War delayed a planned 1914 challenge. He equipped Erin as a hospital ship and gave her over to the Red Cross. The following year she was sunk by a German submarine.

“He says very publicly on a number of occasions, I would give it all back, I would give everything back if I could save any of those who served on that ship,” says Laurence Brady.

Lipton was to make two more bids for the America’s Cup – coming tantalisingly close to success in 1920 but “that auld mug”, as he called the trophy, always eluded him.

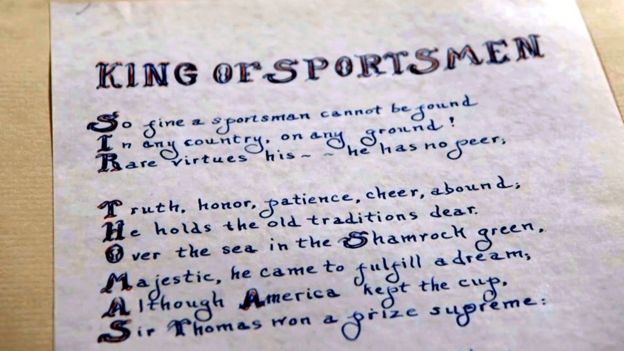

But the good grace with which he accepted defeat earned him goodwill and admiration across America.

After his fifth and final attempt in 1930, the Hollywood actor Will Rogers began a campaign, asking the American public to donate a dollar to purchase a gold “loving cup” to celebrate the perseverance and sportsmanship of the world’s “most cheerful loser”.

Presented to him by the Mayor of New York, the lid was decorated with carved shamrocks. The inscription read: “In the name of hundreds of thousands of Americans and well-wishers of Sir Thomas Johnstone Lipton.”

He died the following year, bequeathing much of his fortune to his native Glasgow.

Huge crowds lined the streets as the funeral cortege made its way to the Southern Necropolis, where he is buried less than a mile from the Gorbals street where he was born.

Today the Lipton grocery chain is largely forgotten, subsumed by mergers.

His name lives on mainly as a brand of tea, now owned by Unilever. But for modern day entrepreneurs like Duncan Bannatyne, he remains an inspiration.

He says: “Tommy never did win that blooming cup – but he won something far greater.

“The love, respect and admiration of people from all walks of life, from around the world. That makes him a winner in my book.”

The Man Who Charmed the World will be broadcast on BBC2 Scotland at 21:00 on Tuesday 25 September and is available on the BBC iplayer.

source:-BBC