When I reviewed Event[0] last month I said, “This might just be one of the most importantindie games of the year.” And then along came Virginia.

Like Event[0], Virginia belongs to a growing subset of experimental games, ones focused on expanding the language of games as much as—or sometimes more than—commercial appeal or approachability.

Whether or not their individual experiments are successful, I feel these games are important to experience if you care about the growth of the medium—not least because you can expect their better ideas to be “borrowed” by the bigger-budget games of the future.

Lynchian

Long preface aside, I don’t think Virginia is a particularly successful experiment.

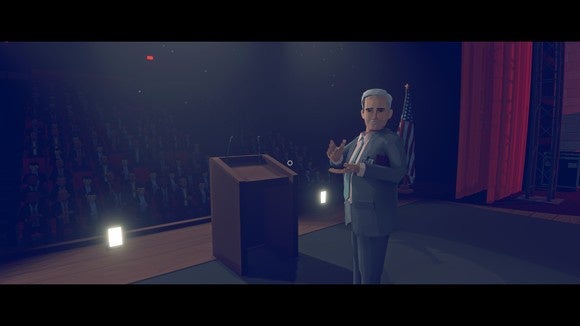

You play as FBI Agent Anne Tarver, a recent graduate of the academy who’s ostensibly assigned to work a missing persons case. This is pretense, though. Your main charge is your partner, Maria Halperin, who you’re investigating as part of an internal affairs matter.

Never before, not even in the heyday of ‘90s full motion video, have film and games drawn so close together. What initially purports to be some sort of detective game is essentially a two-hour short film where the player is occasionally required to click the mouse.

It raises questions about interactivity. How much agency do you need to give the player for a character to resonate, for a game to instill that very particular sort of empathy unique to this medium? We keep pushing this idea further and further.

“Okay, Telltale games are sort-of like a long, semi-interactive movie but controlling the dialogue seems to keep players interested and build empathy. Can we go further? What about a game where you just walk around a family’s home? That still works? Okay, let’s go further still.”

Virginia dispenses with even the trappings of a game in the traditional sense, instead co-opting the visual language of film and television. Letterboxing, sure. Thirty frames per second, sure. But mostly I mean its heavy reliance on jump cuts and match cuts—a nod to Thirty Flights of Loving in the end credits is almost unnecessary, as it’s clear whereVirginia’s inspirations lie. You’re in the middle of some action, and then suddenly you’re teleported through time and space to the completion of that action.

So a long drive through the countryside is instead presented as three short clips, the sun arcing across the sky and the scenery changing outside the windshield. Or a walk to the basement is ten seconds of a hallway, ten of you walking downstairs, and then ten of wandering the basement itself.

No matter that we’ve abridged time and space. The cut is a standard part of film, excising the boring bits to tell a more concise story or draw the audience’s attention to matters it might not notice otherwise. With over a hundred years of film behind us, we’ve grown accustomed to the jump cut as it exists in filmed media.

But it’s decidedly non-standard in gaming, and its use in Virginia is somewhat novel, allowing for trippy dream sequences and a larger sense of scope than could be handled if the player had to physically travel to each location. A whole town can be rendered in a few key points.

The downside is it undercuts the very same empathy games are so brilliant at establishing. Despite some criticism from vocal parts of the games community, the so-called “walking simulator” genre has mostly been successful in its own way, I think because there’s something psychologically satisfying about controlling even an aspect as basic as a character’s movement, of charting a space on your own terms.

Virginia excises that last bit of agency, instead aiming to both railroad players through a story and to disorient. As a result, it’s hard to feel any attachment to the characters or the town of Kingdom, Virginia.

An aside: It could be argued that this is done on purpose, as in Bertolt Brecht’s distancing effect. From this viewpoint, Virginia purposefully pushes the audience away emotionally in order to focus it intellectually on the injustices of our political system, or America’s relation to race/gender. This is a possibility, but I think it’s more likely that Virginia tried to instill true emotional empathy with its characters and failed by nature of the game’s structure.

And that’s partially because the language of film isn’t really translated into Virginia. Superficially, it works. There are film-esque jump-cuts and it makes for an intriguing visual style. But we don’t get the benefits of other important film techniques—different shot types, or framing, or the other elements that make up a coherent scene.

The lack of dialogue certainly doesn’t help either. I actually love Virginia’s lo-fi style, and think the game creates some strong environments out of fairly simple tools. But the lack of dialogue puts a larger burden on Virginia’s animations—particularly its faces—to communicate emotion to the player, and that’s difficult when characters have all the expressiveness of a wooden doll.

And then there are genre concerns. I think a detective story was perhaps Virginia’s gravest error, if only because it implies some sort of investigation or—dare I say it?—interaction on the part of the player. Even in mystery novels, half the appeal is trying to solve the story before the characters. What often makes a good mystery is feeling like all the pieces were there, if only you’d been able to put them together.

Virginia’s mystery is set-dressing though, and is of secondary concern to a more character-centric vein of storytelling layered on top. That’s not bad in-and-of-itself, but in a game already set on subverting so many player expectations it’s just another layer of abstraction between the audience and the game’s emotional core.

But as I said up top, I think Virginia will prove to be one of 2016’s most important indie games even if it’s not entirely successful, and I meant it.

Games are just starting to experiment with the language of film in an artistic way, rather than as mere utility (i.e. cutscenes). I expect that trend to continue, and Virginia adapts film editing in a far more audacious manner than Thirty Flights of Loving or evenQuadrilateral Cowboy.

Virginia also makes extensive use of symbolism—still a rarity in games, which is baffling considering its importance in storytelling and its pervasiveness in other mediums. Virginiaisn’t especially sophisticated in its approach. Its symbols are rather ham-handedly presented to the audience, and ad nauseum.

Nevertheless, there’s something to be said for a game that works in subtext, that encourages a deeper reading of the story beyond “What you see is what you get.”Virginia’s recurring bison and bird motifs may be overdone by the standards of film/TV, but their mere presence is still sophisticated vis-a-vis stories in video games.

Bottom line

I don’t like Virginia, nor do I think it’s successful in accomplishing what it set out to achieve, but I do think someone’s going to look at it and be inspired, and maybe that person will make something great. Or maybe the person after that.

And so we throw Virginia into the growing pile of games I think are important for people who care about the avant garde in gaming—alongside The Beginner’s Guide, Papers Please, Event[0], Soma, and others. These games are almost all flawed in some way, and our scores often reflect that fact, but they’re important. They broaden the way we discuss games, even as they change what games discuss.

source”gsmarena”