If it feels like your wallet is finally getting a taste of that cheap oil that has been unsettling the market for weeks now, you’re right.

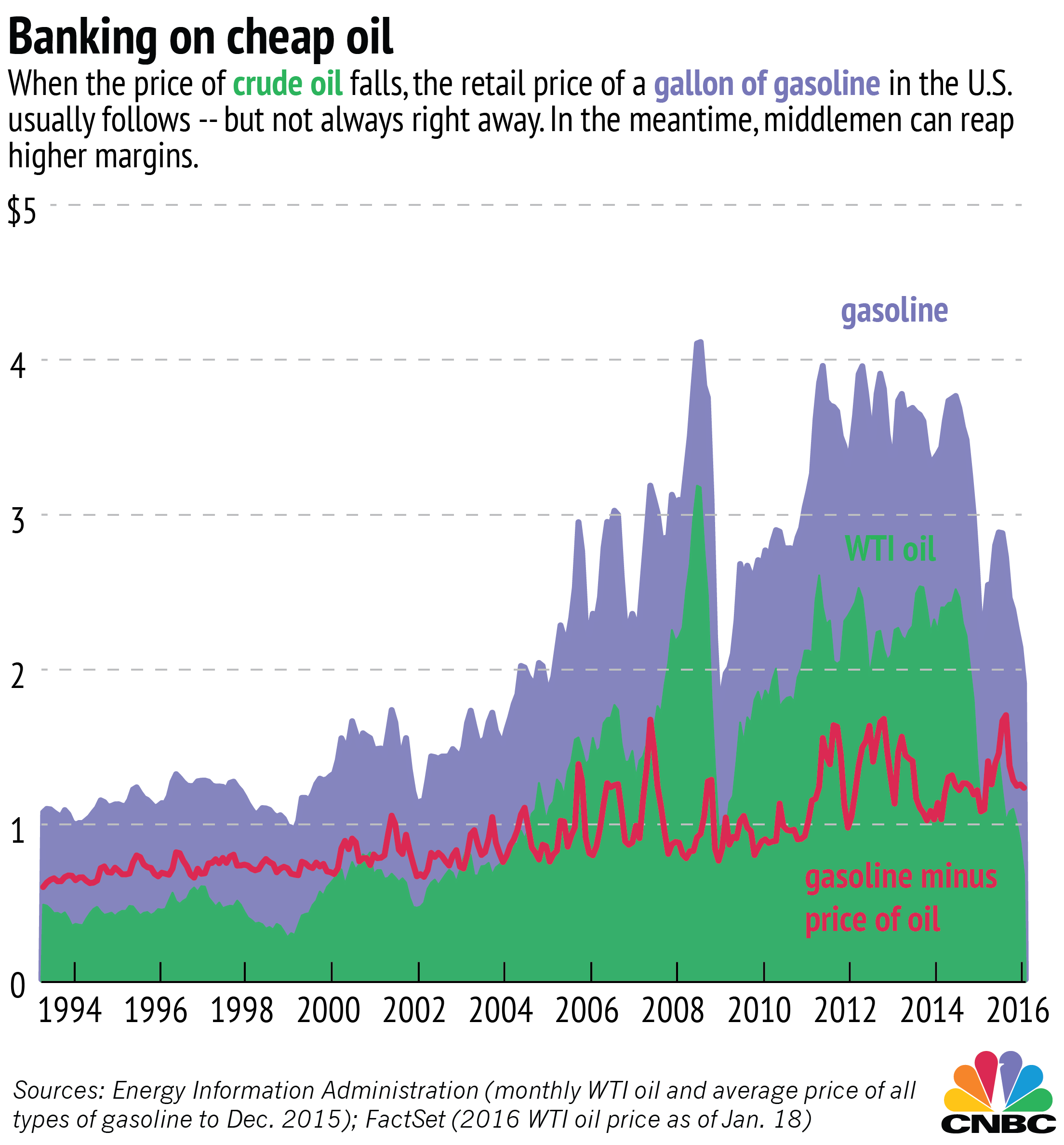

WTI crude oil was down to a little under $30 a barrel earlier this week from the recent peak in the summer of 2014, or about $1.85 on a per-gallon basis. At the same time, data from the Energy Information Administration show that the average price of gasoline is down about the same amount to $1.90. That means the savings from the world’s massive oversupply of crude are making their way into American gas tanks.

Now, you may think that’s just fine and natural. But in reality, the changing price of gasoline seldom lines up exactly with the changing price of the raw materials that make up about half the cost.

Studies show that when oil rises, gas goes right up along with it, but when oil prices fall, it tends to take a little longer for gas prices to adjust. In those opportune periods all the companies between the oil producer and consumer take a piece of the savings if they can.

We saw it last summer — a gallon of oil fell until it was $1.30 cheaper, but gasoline dropped only about 89 cents. In August, the gap between the price of oil and the price of gasoline was $1.70, the largest it’s beensince the EIA started keeping track.

So where does the approximately half a dollar per gallon of missing savings go when the price of gasoline doesn’t fall as quickly as the price of oil? Depending on market conditions, it goes either to the refiners, who take crude and transform it into gasoline and other products, or distributors and marketers, who move the final product to your local gas station and charge you to put it in your tank.

That balance depends on the price of the gasoline leaving the refineries — for example, if a refinery has an unplanned outage like the one that took place in the Midwest last August, but consumer demand remains high, refineries can charge more for their product. If demand is high but gasoline is plentiful, distributors have the upper hand.

According to data from the Energy Information Administration, both refiners and distributors/marketers have been charging more for their services in recent years. Together, they each accounted for about 20 cents of the cost of a gallon of gasoline in 2000, but last year distributors made about 34 cents per gallon and refiners made 49 cents per gallon. That’s far more than the 8 cents they would have gained through inflation alone.

Refiners and marketers gain both from periods of high demand and from slumping prices, while producers are squeezed by the glut of extra crude.

The biggest energy companies like Exxon Mobil and Royal Dutch Shellcontrol nearly every stage of their own operations. So as energy production revenues have fallen they’ve been able to make up some of the difference with their downstream refining businesses. But the good times may be coming to an end.

If refinery capacity increases or demand falls, refiners could see their margins fall. According to BP’s data, global refining margins are down to $12.50 a barrel so far in 2016. That’s down from nearly $20 a barrel a few months ago and $15.26 in the first quarter of 2015 (margins are usually lower in the winter). As a rule of thumb, each $1 decrease in margins costs the company $500 million in annual pretax operating profit, according to its website.

That’s bad new for refiners but good news for drivers, who may find that that money coming to them as price cuts at the pump.

[“source -cncb”]