The reason for its silence may go back 10 years, to when Microsoft product manager Shanen Boettcher demonstrated voice dictation inside Windows Vista—and flubbed it. The technology kept a low profile after that, and today, few users know you can dictate a document within Windows.

If there were ever a time for Windows to try again, though, it would seem to be now, when advances in computers and artificial intelligence provide a much better foundation for the technology. “

“This is such a great question,” said Harry Shum, the executive vice president overseeing Microsoft’s speech-recognition research, as well as Cortana and Bing, when asked about dictation’s future within Microsoft Office. “There is really no reason why it is not playing a much more prominent role yet.”

We decided to give it another chance: We delved into Windows’ voice dictation features to see how they compared to more recent speech-based technologies.

Why speech recognition can’t be too perfect

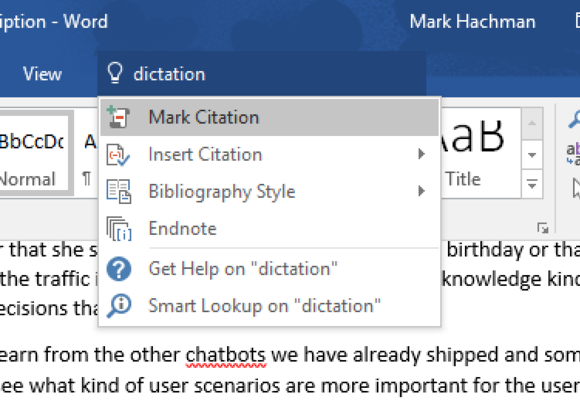

Some of us still think about voice dictation in the same way Doonesbury lampooned the Apple Newton, turning “I am writing a test sentence” into “Siam fighting atomic sentry.” And you’d be forgiven for thinking so, too: Windows Speech Recognition is powered by the Microsoft Speech Recognizer 8.0, which has remained literally unchanged since Vista. Shum called it a “grandpa” technology.

What has changed, however, is the hardware: Listening for and interpreting speech requires far less processing power than a decade ago. The quality of integrated array mics within PCs like the Surface Book mean that dedicated headsets aren’t necessarily required to achieve superior accuracy. Voice dictation for the masses is here, right?

When I tested Windows’ speech capabilities, however, I experienced firsthand the merciless perfection that’s required for the system to be usable. This story has 1,028 words in it, including subheadings. If you used voice dictation software to write it, a 95.0% accuracy rate would mean you’d have to correct more than fifty mistakes. That gets old fast.

In my tests, based on a methodology I developed for another speech recognition product I’m testing, Windows produced an accuracy rate of 93.6%, That’s pretty bad on paper, and somewhat behind the dedicated software I’m trying. Windows also had an odd habit of interjecting the word “comma” when I was dictating the punctuation mark. The speech community seems split on whether relatively minor mistakes like this are significant.

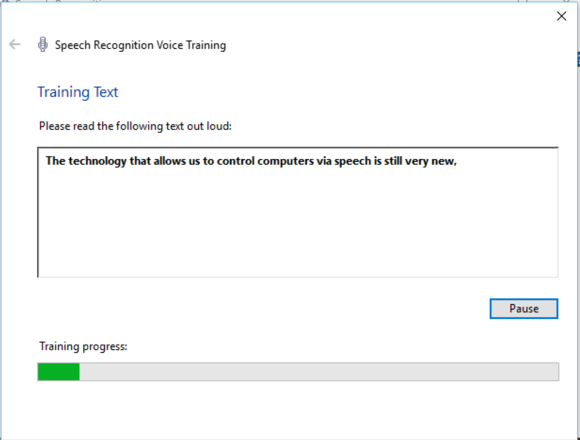

That, of course, was just the baseline. As anyone who’s used dictation software can tell you, the key to accuracy is training. Over time, a voice dictation program learns your accent, whether you pronounce the “a” in apricot like “bad” or “ape,” and how to filter out our unconscious verbal tics. I’ve seen Microsoft employees claim that, properly trained, Windows’ speech recognition was 99% accurate. Ten mistakes or so per 1,000 words isn’t bad at all.

Very few of us, though, probably want to spend the time training the software. Windows Speech Recognition requires up to 10 minutes to run through a few practice sentences, and it feels like a lifetime. Cortana and Siri don’t require any of the same setup time, as they’ve already been trained on millions of voice samples. There’s something to be said for instant gratification.

What makes Cortana (which you can use on your PC or phone) so much better than Windows’ own ancient voice dictation systems is her link to the massive computational power of the Microsoft cloud. Microsoft can crunch and correlate your voice input together with whatever other data Microsoft knows about you, generating the intelligence that is the soul of Cortana.

Microsoft talks up speech recognition

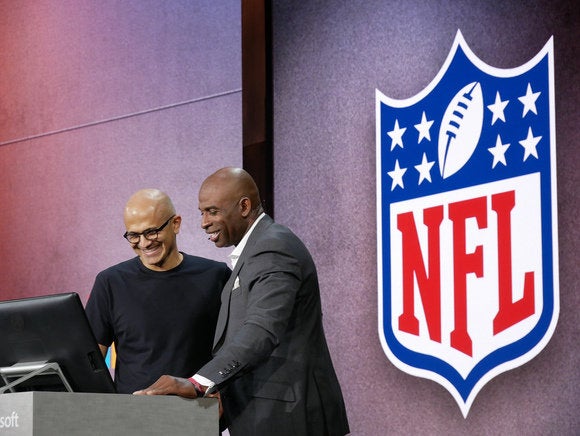

Given Cortana’s proven skills, you’d think speech would have taken center stage at Microsoft’s Ignite show last week. But Ignite contained exactly zero sessions on voice dictation and apparently just one on speech recognition. Meanwhile, CEO Satya Nadella’s keynote address painted speech recognition as a critical component of Microsoft’s future.

Take Skype Translator, for example. Microsoft’s Star Trek-like universal translator depends upon three different strands of research, according to Nadella: speech recognition, speech synthesis, and machine translation. “So you take those three technologies, apply deep reinforced learning and neural nets and the Skype data and magic happens,” he said.

“Even inside of Word or Outlook when you’re writing a document we now don’t have simple thesaurus-based spell correction,” Nadella added, adding that Office can now even compensate for dyslexia. “We have complete computational linguistic understanding of what you’re building. Or what you’re writing.”

But not what you’re saying, apparently.

Microsoft

During the same speech, Nadella bragged that Microsoft’s speech algorithms achieved aword error rate of 6.9 percent using the NIST Switchboard test. That sounds bad: that’s accuracy of about 93.1 percent. But the Switchboard test uses sample rates of just 8KHz, about the quality of a telephone conversation in the year 2000. Windows Media Audio 10, the codec within OneNote, can capture audio at up to 48KHz, providing much more accurate samples.

I think it’s pretty obvious that the pieces of the puzzle are there, technically. If there’s any obstacle, it might be organizational: As of Thursday, Microsoft’s Office apps were spun out into their own group, away from Cortana and Bing. Shum, however, said that intelligence is still part and parcel of Microsoft’s offerings. “Rest assured that we are infusing AI technology into all Microsoft products,” he said.

It’s possible that Microsoft believes that offices won’t want workspaces filled with the clamor of workers dictating over one another. Or perhaps Microsoft truly believes that its existing speech recognition capabilities within Windows are sufficient to enable dictation for the masses.

If Microsoft truly believes in productivity, though, the future of speech recognition within your PC probably isn’t using Skype to book a hotel in Bangladesh. It’s writing about the experience—but with your voice rather than your fingers.